In the second blog of our new series Understanding Evidence, Iain Chalmers, our founding director, looks at developments in research on prenatal corticosteroids since the work which gave rise to the Cochrane logo. Join in the conversation on Twitter @iainchalmersTTi @CochraneUK#understandingevidence

The birth of the Cochrane logo

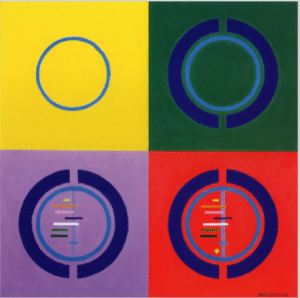

David Mostyn’s design for the Cochrane logo

Twenty four summers ago I asked David Mostyn to design a logo to illustrate the objectives of the soon-to-be-opened Cochrane Centre. He did a good job: the circle reflects global objectives and international collaboration; the mirror image ‘Cs’ stood for the Cochrane Centre (and, a year later, the Cochrane Collaboration); the horizontal and vertical lines show the results of some early randomised trials assessing the effects of prenatal corticosteroids on the likelihood of early neonatal mortality; and the diamond is a statistical summary of the information derived from the individual studies above it. As prenatal corticosteroids were not in widespread use at the time, the logo illustrated the human costs that can result from failure to prepare systematic, up-to-date reviews of controlled trials of health care.

The story of prenatal corticosteroids has been documented in a Wellcome Trust Witness Seminar: among other contributions, Patricia Crowley, an Irish obstetrician, described her initial systematic reviews of controlled trials of prenatal corticosteroids, and I described how the Cochrane logo came to be designed. At the inaugural Cochrane Colloquium in 1993, Andrew Herxheimer presented the directors of the four Cochrane Centres and their administrator colleagues with wrist watches with faces based on the Cochrane logo (mine is still going strong).

Iain’s Cochrane logo watch is still going strong!

Over subsequent years, the Cochrane logo has gradually achieved iconic status and become very widely associated with independently prepared, high quality systematic reviews of research evidence. Patricia Crowley’s original review (1) was updated and extended by Devender Roberts and Stuart Dalziel (2) [Stuart works at the same Auckland, New Zealand, hospital at which the first, ground-breaking trial of steroids had been done and reported in 1972 (3)]. Prophylactic prenatal corticosteroids became very widely adopted, particularly after they were endorsed in the early 1990s at a consensus conference organised by the Office of Medical Applications of Research of the US National Institutes of Health. And in 2012 and 2013, the UN Commission on Life Saving Commodities and Save the Children both recommended rapid, worldwide ‘scale up’ of prenatal corticosteroids (4).

Might prenatal corticosteroids actually be harmful?

This widespread consensus was challenged in 2014 when Kishwar Azad and Anthony Costello fired a warning shot in a Lancet commentary (4) entitled ‘Extreme caution is needed before scale-up of antenatal corticosteroids to reduce preterm deaths in low-income settings.’ They warned about the dangers of using steroids without adequate ‘level 2’ neonatal care, and referred to alarming evidence in populations in which the prevalence of malnutrition and the risk of sepsis are high and access to antibiotics is low.

The ‘alarming evidence’ to which Azad and Costello referred was published in The Lancet on 14 February 2015. Fernando Althabe and his many colleagues published a large randomised cluster trial done to assess the effects of a multi-faceted intervention designed to increase the use of prenatal corticosteroids at all levels of health care in low-income and middle–income countries. The results did not endorse the message that had been conveyed in the Cochrane logo and in the current version of the relevant Cochrane review (2). Instead, the new study estimated that for every 1000 women exposed to the steroid use scale up strategy, there was an excess of 3.5 neonatal deaths and increased maternal infection (6), and secondary analysis suggests that this increased mortality was attributable to differential exposure to prenatal steroids (7).

This information is clearly of immense importance. An update of the relevant Cochrane review is currently going through the editorial process with the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group (7). However, the trial reported by Althabe et al. (5) will not actually meet the criteria for inclusion in the updated review. This is because it is not an evaluation of the effects of steroids – an intervention of establish benefit – but rather an evaluation of the effects of an intervention to scale up the use of prenatal steroids (Zarko Alfirevic, personal communication).

WHO’s prompt response to important new evidence

WHO responded promptly to the new evidence by amending its preterm birth guidelines: these now state that steroids should be used only when an accurate assessment of gestational age is available; when preterm birth is considered imminent; when there is no evidence of maternal infection; and in circumstances where adequate childbirth and neonatal care is available.

WHO has also sponsored a new trial comparing steroids with placebo in women at high risk of preterm birth between 26 and 33 weeks gestation in level 2 hospitals in low-income and middle-income countries (Fernando Althabe, personal communication). It will clearly be important for the updated Cochrane review to refer to this study.

As Kathy Burgoine and her colleagues in Uganda wrote in response to the report by Althabe and his colleagues:

To ensure that every neonate who might benefit from antenatal corticosteroids does, great urgency is now needed to clarify in which neonates these drugs will be beneficial. Antenatal corticosteroids might have no role in settings of high-infective morbidity, alternatively it could be that for these drugs to be beneficial they need to be given in conjunction with antibiotics and other infection control measures. (8)

But antibiotics may cause, as well as reduce, problems. Routine administration of antibiotics before membrane rupture in preterm labour may indeed reduce the number of women who develop infections; but this policy may also result in an increase in neonatal deaths and enduring functional impairment (9). As suggested by Azad and Costello (4), drugs alone are unlikely to meet the needs of childbearing families in low-income and middle-income countries.

When should a Cochrane systematic review be regarded as ‘closed’?

In 2015, Yves Lacasse and his colleagues in the Cochrane Airways Group declared that their review of the effects of pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was closed because the results, based on 65 controlled trials, had become ‘stable’ (10): further updating was highly unlikely to modify its relevance for the foreseeable future (measured in years rather than months). Their review thus would now seem to provide a solid basis for informing practice and policy, and for challenging any proposals to do yet more trials addressing the same question as likely to be unethical and a waste of precious resources (www.ebrnetwork.org).

The Cochrane review of corticosteroids for women at risk of preterm birth (2) confirmed in 2006 that research done over the three previous decades had validated the message conveyed fourteen years earlier in the Cochrane logo. Not unreasonably, some people may have concluded that the issue had been settled and that the review should now be regarded as ‘closed’, not in need of any further updating, and should influence policy worldwide. The findings reported by Fernando Althabe and his colleagues (6) have reminded us that things are not quite as simple as they may once have seemed to have been.

The continuing evolution of evidence about the effects of prenatal corticosteroids is simply the most recent illustration of the importance of confronting the daunting challenge of providing up-to-date, reliable evidence of the effects of health care.

Iain Chalmers

James Lind Initiative

1 September 2016

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Zarko Alfirevic, Fernando Althabe, John Castle and Jack Leahy for comments on an earlier draft of this commentary.

References may be found here.